I started writing a post about washi tape, but realised that before I get to that I’ve got to take a closer look at washi itself. I’ve encountered the discussion of “what is washi” repeatedly over the last few years, and I’d like to examine the origin, meaning, and usage of the word washi.

So, what is washi?

Let’s start with the kanji characters. wa (和) =Japan, and shi (紙) = paper, so washi (和紙) is Japanese paper. So far, so good.

So then, what is washi (Japanese Paper)?

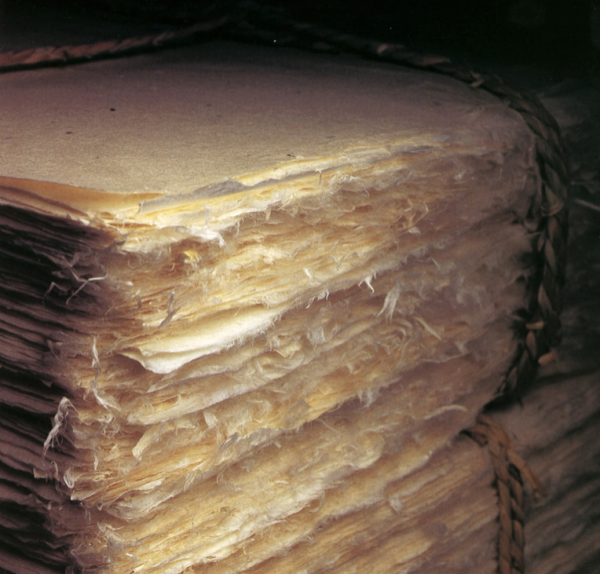

If you asked 10 random people to describe washi, you’d get back 5 or more different answers. For some individuals, the word washi conjures up images of thin, soft, delicate sheets of natural-coloured handmade paper. Others might imagine richly coloured sheets, made with various natural dyes and pigments in varied patterns. For others the same word means papers in a variety of boldly coloured, often intricately detailed, heavily printed papers. Still others think of paper used for origami, the craft of paper folding, or of machine-made papers of innovative design and subtle sensibility. Another possibility is thin papers patterned to look like a kind of lace. The list goes on.

So, what is washi, really?

Let’s start with the beginning. Tsai Lun supposedly invented papermaking in China 1900 years ago (likely a non-truth, but that’s another story for another time). Was this Washi? No, of course not. It was Chinese paper. Ok, next. Priest Doncho brought papermaking from Korea to Japan 1400 years ago. Was this washi? Well, when it first entered Japan it couldn’t have been Japanese paper yet, so no. How about 100 years down the road? Finally, we’re getting close, something we can sink our teeth into — maybe this was Japanese paper, but it was still not called “washi” by anyone, so can we say it was washi? Hmm, not sure. Next we have the development of nagashizuki, what is usually considered the prototypical Japanese paper production method, probably about 1200 years ago. Was this washi? … Probably. In my mind paper from this period is the easiest thing to call Japanese paper (because its particular way of being made was developed in Japan by Japanese for Japanese), but the word washi still didn’t exist yet! The word paper (kami 紙) existed, but not washi. Jumping forward to paper made in the period just before the opening of the country to trade, around 150 years ago — was it washi? It had to be, right? With no outside influence this had to be quintessentially Japanese paper. But it still wasn’t called washi yet! So, next we have the official opening of the country around 1850, and around the same time the widespread introduction of foreign paper and soon thereafter western papermaking technology. The need for a name for Japan-made paper, as opposed to foreign-made, arose at this time, and the word washi came into use. Of course initially, this was hand-made, exclusively of traditional Japanese bast fibres kozo, mitsumata and gampi, but in time papers made with other fibres and even on papermaking machines also came to be called washi. Recently, even papers made outside of Japan that have a certain look or feel have been spotted labeled as washi.

It’d be nice if we could just say “paper made by hand in Japan”, but it’s just not as simple as that. Let’s look at some different papers and try to decide which is washi and which is not. We’ll start with some relatively easy ones, and work our way into some more difficult ones:

• Machine made in Japan from Japanese kozo? Does the machine-made aspect disqualify it from being “real washi”?

• Handmade by Japanese craftspeople in Africa using local mulberry (kozo)? In today\’s global climate, does location of manufacture or provenance of materials matter?

• Handmade by Taiwanese in Taiwan but to the specifications of a Japanese studio (and sent back to Japan to be sold in Japan or other markets as “Japanese paper”)? Does the maker’s nationality have an effect?

• Machine made from a blend of (imported) wood pulp and kozo, in Japan by a 500 year old Japanese company, using a combination of production methods, some of which are “ancient” or “traditional”? Where do you draw the line?

• Handmade using strictly traditional methods, but using kozo grown in South America?

• Handmade by a Living National Treasure papermaker, but using non-local kozo?

• Cooked in ash, and produced using strictly traditional methods, but dried on heated stainless steel?

The interesting thing here is that there are people on both sides of every one of the above cases, all of which are real, by the way. Some will say it is washi and some will say it is not.

It’s more or less impossible to agree on whether each of these are “real washi” or not! Sadly, even Japanese papermakers don’t have a ready answer. In the end, it looks as though we’ll have to go forward without a clear distinction of what washi is. That makes things difficult for those trying to save it, work with it, or even talk about it, but arriving at a consensus is proving to be even more difficult.

What does the word washi mean to you? Let me know in the comments!